My writings on the Nation, Torah, and Land of Israel. To see my artwork, please visit Painting Israel.

Thursday, May 29, 2008

An Israeli Political Primer

The Moshiach Year

There's a saying that whatever a PM will accomplish during his tenure, he will have to accomplish within the first year. This is what I think of as the "Moshiach" (Messiah) phase, where everyone knows that the PM will not solve any of society's ills, but the voter can still hear that small, soft voice at the back of his subconscious whispering that maybe he will. At any given point during the "Moshiach" year, any election results would probably be roughly the same as they were on election day, so parties have no interest in going to new elections. Most ministers sit tight in the coalition at their various government ministries, milking their positions to feed the party bosses who put them in power. The real estate developers make their inside deals for government land, labor suppliers get their relaxations on worker's visa restrictions, all the business of running a country gets done. Meanwhile, an investigation is reflexively opened against whoever happens to be PM a day after he takes office to prepare a case against him for accepting the illegal campaign contributions from these same real estate developers and captains of industry that every politician requires to win an election. These investigations provide the attorney general with much-needed press exposure, as his position is seen as a stepping stone to the supreme court, which holds the real power over Israeli society.

Things Get Shaky

After his first year as PM, as the population grows dissatisfied with whoever happens to be in power, and public opinion polls start showing that one of the parties in the coalition would stand to gain a few seats in the Knesset (parliament) by bringing down the government and going back to the polls. With nothing to lose and everything to gain, this party begins to push and shove for more of the public revenue, a bigger spot at the trough. Meanwhile the other little parties get anxious that the PM will begin to favor the threatening party and take away their own money supply, and so they begin to threaten to bolt the coalition as well. Often the PM's leash-holders in the American administration shake things up as well, demanding Israel reduce the burden on the "Palestinians" by removing checkpoints and reducing security, which invariably results in some sort of terrorist atrocity and further reduces the credibility of the PM and his party.

The Death Spiral

In stage three, the "Death Spiral," one of the parties in the coalition, having extracted every last shekel possible, bolts, or an investigation comes close to fruition. At this point, the PM begins flailing like a drowning swimmer, throwing promises and benefits in every which direction as the vultures swoop in for a piece of the carcass. Sometimes the PM can bribe a smaller party to shore up his coalition for a few months with all sorts of political and financial goodies. Whichever parties remain in power demand greater influence until the system comes crashing down and new elections are called.

During the elections, the media anoints a new leader as Moshiach, who is promptly elected. All investigations against the outgoing prime minister are dropped, and the now ex-PM travels to America to make millions in various business deals before returning in a few years to plan his political comeback. Meanwhile, corruption charges are filed against the new PM.

I used to be enamored of Israeli democracy before I knew better. I even imagined getting involved on some level. But Judaism teaches us that when one enters a position of political power he loses his free will. The leader may feel like he is making his own decisions, and he is still held accountable for them, but in reality he's just a tool of higher forces. The politically powerful person becomes something like a caged animal, so enchanted by the trappings of office he is willing to do anything and forgo all his principles to hold them.

But the one who steers the direction of society, beyond the Supreme Court, is the interest group. These small groups of dedicated people can focus all their energies on one agenda and slowly chip away at the body politic until they have created an entirely new reality. Peace Now, for instance, has managed to take positions such as negotiating with terrorists and establishing a Palestinian state, which thirty years ago were considered so odious and treasonous they existed beyond the fringe of civilized discussion, and has now turned them into positions so cliché they bore you to tears. Likewise, the Hareidi parties have built extensive yeshiva systems, permanent army exemption for themselves, and managed to create the relatively sheltered existence from Israeli society. The National Religious have managed to create a network of Jewish settlements across the land of Israel despite worldwide political protest, perennial Arab violence, and the determined domestic opposition of the more liberal parties.

But to have a real effect on society, at a most basic level, most important thing a Jew in Israel can do is live a kosher life, raise a decent family, and pray three times a day for a real Moshiach to get us out of this mess.

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

Rav Mordechai Eliyahu

Last Tuesday he went to the hospital for one of his regular physicals. While he was there, he went into cardiac arrest. Thank God, he happened to be at the hospital at the time, and so doctors were able to save his life. However, he remanis in serious condition, so an emergency gathering was called to the Kotel (Western Wall) to pray for his speedy recovery.

Sheets were passed out with Tehillim (Psalms) in order beginning with the letters of his name.

Sheets were passed out with Tehillim (Psalms) in order beginning with the letters of his name. The Kotel was pretty full. People came in from all over the country.

The Kotel was pretty full. People came in from all over the country.

Impassioned prayers went on for hours and hours, into the night.

Impassioned prayers went on for hours and hours, into the night.Sunday, May 18, 2008

NBN Tiyul to Haritun Cave

But the Haritun cave, well, there's something new.

Walking on the trail to the cave, there seems to be some sort of ruins. My guess, based on the relatively well-preserved state of the ruins, is that they're Byzantine. But that's just a guess.

Of course, some of us have been taking photography lessons and want to put them into practice.

Impossible building.

Impossible building.As mentioned in previous posts, this area of the Judean Desert is riddled with caves, and have always made ideal hiding places when the frequent Jewish revolts against whichever empire happened to be opressing us at the time went awry. But this cave wasn't carved out by scraggly Jewish rebels with hand axes hiding from the armies of Rome. It was carved out by natural forces millions of years ago (am I allowed to say that on a kosher blog?) when this region was submerged (hey, maybe it was during the great flood) and streams of acidic water carved tunnels and crevaces through the rock.

Of course, there was a bit of a wait to get in. The narrow entrance allows only one person at a time.

But once you get in the cave, it looks pretty much like this:

After smashing your head into a few stalagtites (or is it stalagmites), you gradually learn how to walk through a cave. Wave both arms in front of yourself as you walk. If you're going to stand up, place your hand about one foot above your head, and put your tip toes forward before shifting your weight onto your foot, to make sure you don't go careening over a cliff or something.

The cave is actually a network of caves, and it extends over about 5 kilometers, so it's easy to get lost. In order to avoid becoming an archaeological relic yourself, you've got to keep an eye on a cable that runs along the ground.

There were some places where the cave was only about 3 feet wide by 2 feet high, so you have to crawl on your belly just to get through. I couldn't even rest on my elbows, I had to swim through the dirt. Not for the clausterphobic.

Crawling through the narrow spot, which we called the "Birth Canal." The Hanzel-and-Grettel cable is to the left.

Crawling through the narrow spot, which we called the "Birth Canal." The Hanzel-and-Grettel cable is to the left.

Of course, you can never stand up for long.

It really was a terrible attack, during the beginning of the intifada. It's the sort of thing that anyone who was here at the time can never forget. Kobi's parents began a foundation to help grieving relatives of similar attacks, including a camp for bereaved children.Chava, getting dirty for the shot.

Wednesday, May 14, 2008

Herodion 7: Renewed Jewish Life near the Herodion

To the south is Tekoa, home village of Amos the Prophet. Despite the fact that it's outside the security barrier, the new road opened recently has reduced commute times to Jerusalem from 45 minutes to 10 minutes. Housing prices have shot up and new trailers pop up everywhere.

Tekoa

Tekoa

Small patches of trailers mark the new areas settled by the residents of Noqdim. Out into the distance are the rolling hills of Judea. In the far distance, on a clear day, you can see the Herodion.

Small patches of trailers mark the new areas settled by the residents of Noqdim. Out into the distance are the rolling hills of Judea. In the far distance, on a clear day, you can see the Herodion. The region is also populated by a smattering of Bedouin, now post-nomadic, who settled in the region during the Jordanian occupation, between 1948 and 1967. One trend I have noticed over the past few years is the Arabs' switch from plopping down individual houses to building massive tract-housing projects, likely something they picked up working as laborers on Jewish land developments.

The region is also populated by a smattering of Bedouin, now post-nomadic, who settled in the region during the Jordanian occupation, between 1948 and 1967. One trend I have noticed over the past few years is the Arabs' switch from plopping down individual houses to building massive tract-housing projects, likely something they picked up working as laborers on Jewish land developments. Tract housing in the middle of an Arab village. Five years ago you never saw something like that.

Tract housing in the middle of an Arab village. Five years ago you never saw something like that.After the tour, we took a break in Tequoa to see the new olive press just opened there, and to scarf down some lunch.

And that's it for the Herodion!

Monday, May 12, 2008

Herodion 6: The Jewish Rebels

This hole, which Herod would have considered unsightly in the midst of his fine garden, was actually a mikveh, a Jewish purity bath, dug out by the Jewish rebels over a century later as they took control of the fortifications.

|

| King Herod's Palace Inside Herodion |

|

| Yours truly, inside the Herodiom |

|

| Herod's Grave |

The smashed ruins of Herod's grave. Guess he doesn't even have a grave to roll in any more.

The smashed ruins of Herod's grave. Guess he doesn't even have a grave to roll in any more.

Friday, May 09, 2008

Herodion 5: Upper Herodion

Previous posts in this series:

Herodion 1: Givat HaArba

Herodion 2: Who was Herod?

Herodion 3: Lower Herodion

Herodion 4: Cisterns and Tunnels

The palace above was where the true work of Roman rule was accomplished. Only invited guests could reach its gate. One steep ramp provided access.

Arches over what was once the front gate, now being excavated.

Herod himself would be carried up the steep slope in a chair by his obliging slaves.

The upper palace, looking west.

The open courtyard, surrounded from the outside world by high walls, must have been a sight to behold.

On the east and west ends, columns supported a roof for shade. In the center was a garden.

Columns supporting shade structures. You can almost picture the ancient couches on which Herod must have rested his tired, megalomaniacal head.

Columns supporting shade structures. You can almost picture the ancient couches on which Herod must have rested his tired, megalomaniacal head.

As the sun rose in the morning, Herod could enjoy shade on the eastern side, then move to the west after midday as the sun began to set.

Herod's living room (behind the wall.)

Herod's living room (behind the wall.)

In the northeast corner stood the bath house. This was actually, probably the most important part of the palace.

In the northeast corner stood the bath house. This was actually, probably the most important part of the palace. The domed ceiling of the cold room still stands.

The domed ceiling of the cold room still stands.

Any proper Roman Aristocrat had a bath house of his own. Probably sitting for several hours at a time in his sauna, this is where Herod invited guests, planned his moves, and made his deals.

Looking back over the ruins.

Thursday, May 08, 2008

The Herodion

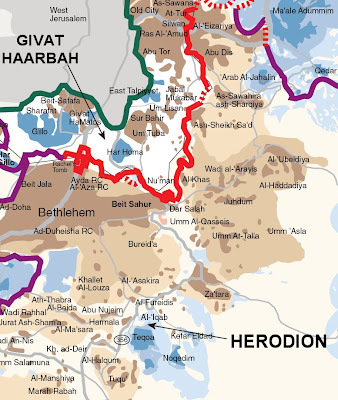

TO the north is Kibbutz Ramat Rachel. This Kibbutz was founded in 1926. As was true for the entire country, the facts on the ground set the borders of the state. Because the Kibbutz was able to survive the Jordanian invasion of 1948 through to the end of the war, the "Green Line" was drawn to include it. The border ran right through the valley in between them (shown below.)

Closer Up

To the west is the "contraversial" building project of Har Homa. This hill, which was across the border, housed the remains of a Byzantine era defensive fortress. The only clearly visible remain from a distance was the "Wall," or "Homa," in Hebrew. Israeli soldiers guarding the border looking across aptly named it "Har Homa," "Wall Mountain," and the name stuck. Recently, construction of a massive new Jewish neighborhood has been continuing apace, and Prime Minister Olmert incurred the wrath of his American handlers when he approved a few hundred additional housing units there last month.

Har Homa

Har Homa up close

To the south, is Beit Lechem, "The House of Bread," also known as Bethlehem. The birth village of David Hamelech, King David, it is today firmly under the anarchic realm of the Palestinian Authority.

Olive groves and terraces, on what is probably some of the most expensive real estate in the country, and Bethlehem.

Olive groves and terraces, on what is probably some of the most expensive real estate in the country, and Bethlehem.

The spires of churches in the old city of Bethlehem peeking up ober contemporary buildings. Today the city has been largely Islamified, and it seems likely that it will be completely de-Christianized in the coming decades.

A large concrete wall shelters civilization from the Palestinian Authority.

A large concrete wall shelters civilization from the Palestinian Authority.

And off in the distance is the Herodion. It's clearly artificial top, and the lowered top beside it, make it an obvious landmark.

We don't really know what Herod looked like, but we know he descended from Idumeans, the descendants of the biblical Edomites, traditional enemies of the Jews. But over the 1200 or so years between Joshua's conquest of the land of Israel and Roman rule, the Edomites had gradually moved into southern Judea, which the land of Israel was called at the time, and slowly assimilated the beliefs and practices of their Jewish neighbors. After the Jewish revolt in 3597 (136 BCE) overthrew the Seleucid Empire and replaced them with the Jewish Hasmonean dynasty, the newly sovereign Jews weren't sure how to handle this minority. Finally, the Hasmonean kings simply converted them on mass. There are opinions that the conversion was forced, which, by halachah, would have made it invalid. Still, the Idumeans seem to have been absorbed into the Jewish people seamlessly and a few years later, when Judea was conquered by Rome, they did not return to their idolatrous roots but remained faithful to Judaism.

Then the Roman-appointed Idumean ethnarch (administrator) of occupied Judea passed away, his position passed to his son. Judea, being a border province, was subject, like all border provinces, to the occasional barbarian invasion. During one such assault, the Jews took advantage of apparent Roman weakness to try to revolt against the empire and reestablish a Jewish kingdom. Herod, following the advice of his late father, stuck with the romans, and so the Jews came after him. Fleeing on horseback, he, his family, and a contingent of loyal guards, made it about eight miles southeast of Jerusalem when his mother's carriage overturned.

Surrounded by the Jewish rebels, he decided, like a good Roman, that it was time to take his own life rather than be disgraced in capture. As he prepared to die, his mother told him she was not badly injured, to take heart, that he would yet survive. Regaining his will, he managed to fight his way out of the trap and escape to freedom.

Eventually, he made it all the way back to Rome and met with Emperor Octavian. To make a long story short, he managed to receive Octavian's blessing and an appointment as a proconsul-in-exile, and was dispatched with two Roman legions to recapture Judea for the Romans. He made short work of the Jewish revolt, and, in typical Roman style, began a period of mass executions, both of his military enemies, rabble-rousers, and his own political rivals within his family.

Later in his life, with his rule firmly established, he began the construction of a massive palace on the exact spot where he had almost lost his life.

Today, the ruins of this palace, called the Herodion, stick out like a sore thumb from the surrounding Judean hills. For one thing, the mountain ruins of his fortress has an odd flattened top. The hill alongside it has also been shaved down a bit so there should be no competition. Herod spared no slave labor in the creation of his flashy palaces.

The Herodion as it must have looked.

While the Herodion was just as lavish as Herod's other building projects in the holy land, including his renovations of the Second Temple and construction of the Western Wall at which Jews pray to this very day, this project had one major difference. All of its opulence was hidden on the inside. Surrounding the palace was a sheer stone wall which sent a clear message to passers by. "What goes on behind these walls is none of your business."

A view taken from above, peering down into the Herodion itself, illustrates.

Photo not taken by me (our bus didn't fly.)

Photo not taken by me (our bus didn't fly.)

A photo of lower Herodion taken from the top of upper Herodion. Surrounding it are contempoirary Bedouin villages.

A photo of lower Herodion taken from the top of upper Herodion. Surrounding it are contempoirary Bedouin villages.First, we got off our bus on an expansive flat space. In this hilly country, it's pretty clear that this space is not naturally flat, but it was filled and excavated by Herod's engineers. According to Josephus (a Jewish apostate to the Romans,) this area was filled with grass and an olive grove.

Getting off the bus in the flattened area. Imagine it with trees and grass.

Water from the aquifer flowed into an enormous rectangular pool. At the center of this pool was a small island protruding above the waterline. You could swim out to the island or take a small boat to enjoy a picnic.

Pool with small island in the center.

Around the pool, on three sides stood tall columns holding a shade roof for shade.

Roof-supporting columns surrounding the pool.

To the south, between the slopes of Upper Herodion and the pool, are the recently excavated ruins of a large village-like administrative center. To the east of this stood an artificial elevated platform.

Village ruins. The levated platform is today covered with Bedouin olive groves (platform is top left.) This platform was, in its day, used for processions.

Village ruins. The levated platform is today covered with Bedouin olive groves (platform is top left.) This platform was, in its day, used for processions.

In the village, the teltale Herodion stones, with the relief trim carved around the edges.

In the village, the teltale Herodion stones, with the relief trim carved around the edges.

Carved stones and stone bricks, still in ruins.

At the western end, stands a Byzantine church.

A rebuffed attempt to enter the site of Herod's grave, excavations still ongoing.

A rebuffed attempt to enter the site of Herod's grave, excavations still ongoing.

Stay tuned!

The ruins of upper Herodion.

Taking the path that snakes around the hill, we come to the entrance to the underground portion.

This network of three underground caverns was dug out when the hill was much lower, prior to Herod's building up of the palace above. Coated in thick plaster, the walls were completely watertight. This seems to be a system of cisterns. Since they are at a higher elevation than the pool, it seems that they would not have been filled by gravity like the aqueduct-fed pool below. Rainfall on the mountain top was also insufficient to fill the caverns. It seems that these vast caverns were filled, one donkey-load at a time, by slave workers.

Cistern 1. The floor actually goes down much further but is filled with dirt in this case.

Cistern 1. The floor actually goes down much further but is filled with dirt in this case.

Cistern 2, with the floor fully excavated.

Cistern 2, with the floor fully excavated.

A hole in the ceiling, through which people in the palace above would drop buckets into the cisterns to fill up.

Like many structures built by Herod, the Herodion was well-fortified, strong enough to hold up during a Jewish revolt until the legions of Rome could sweep in to the rescue. Like many of these well-fortified structures, it ended up being seized by the very Jewish rebels Herod had hoped to protect himself from, and holding out against Roman siege.

During the Bar Kochba revolt against Rome, 136 years after Herod's death, rebels captured the fortress. Facing the Romans on the open field of battle was suicide, so they began a system of underground fortifications in all of their strongholds. A maze of tunnels, stairways, escape hatches, and drop-offs were carved connecting the cisterns and the palace above.

The goal was to draw the Romans into the network and kill them on unfamiliar terrain. Needless to say, the revolt failed, the Temple was destroyed, the Jewish presence in Jerusalem was completely wiped out, and Jerusalem became a city forbidden to Jews.

Bar Kochba caves riddle the insides of the hill.

Well, it's been a busy two days. Spent yesterday, Thursday celebrating Yom Ha'Atzmaut (Independence Day) with Machon Meir, visiting sites of interest from 1948, and then visiting Mevo Dotan, a settlement in northern Samaria currently on the front lines. Today, I went with MOSAIC, an Anglophonic hiking group, through the forrested hills between Jerusalem and Beit Shemesh on a hike/photography lesson. But now I'm totally sunburned, shabbat starts in a few minutes, and I don't have time to edit the pics, so we'll continue the Herodion tour photos until I get around to posting the other photos. Shabbat shalom!

Previous posts in this series:

Herodion 1: Givat HaArba

Herodion 2: Who was Herod?

Herodion 3: Lower Herodion

Herodion 4: Cisterns and Tunnels

The palace above was where the true work of Roman rule was accomplished. Only invited guests could reach its gate. One steep ramp provided access.

Arches over what was once the front gate, now being excavated.

Herod himself would be carried up the steep slope in a chair by his obliging slaves.

The upper palace, looking west.

The open courtyard, surrounded from the outside world by high walls, must have been a sight to behold.

On the east and west ends, columns supported a roof for shade. In the center was a garden.

Columns supporting shade structures. You can almost picture the ancient couches on which Herod must have rested his tired, megalomaniacal head.

Columns supporting shade structures. You can almost picture the ancient couches on which Herod must have rested his tired, megalomaniacal head.

As the sun rose in the morning, Herod could enjoy shade on the eastern side, then move to the west after midday as the sun began to set.

Herod's living room (behind the wall.)

Herod's living room (behind the wall.)

In the northeast corner stood the bath house. This was actually, probably the most important part of the palace.

In the northeast corner stood the bath house. This was actually, probably the most important part of the palace. The domed ceiling of the cold room still stands.

The domed ceiling of the cold room still stands.

Any proper Roman Aristocrat had a bath house of his own. Probably sitting for several hours at a time in his sauna, this is where Herod invited guests, planned his moves, and made his deals.

Looking back over the ruins.

Note the base of what was once a massive, three-story tower. Note the left edge, where it meets the ground, there is a sort of dark hole in the middle of the garden.

This hole, which Herod would have considered unsightly in the midst of his fine garden, was actually a mikveh, a Jewish purity bath, dug out by the Jewish rebels over a century later as they took control of the fortifications.

Yours truly.

Not only did they build a mikveh, the Jewish rebels converted Herod's own bedroom into a synagogue!

To the left are the ruins of the tower. Below is the bathhouse, and in the background are the hills of Beit Lechem (Bethlehem) and Gush Etzion.

Later in his life, Herod realized that the end was near and had to decide where to make a grave for himself. Since he had almost committed suicide here all those years ago, the Herodion seemed like the perfect location. The sheer walls surrounding his palace were torn down, and the sides filled with dirt instead, transforming the palace into a classical Roman mausoleum. Herod had himself interred on the side of his artificial hill, halfway between the palace above and the resort below, facing north.

No doubt Herod, despite his Jewish roots a fine, upstanding Roman aristocrat, would be rolling in his grave at the idea of his Roman palace of decadence used to fight the very Roman occupation he represented. The idea of synagogues and mikvehs being built right in his pagan palace would be particularly horrifying. Of course, the rebels themselves must have been driven crazy by the idea of that good-for-nothing Roman oppressor buried right in the site they had captured. The remains of Herod's grave were found less than a year ago, smashed to pieces, most likely by the Jewish rebels.

The site of Herod's grave, still being excavated.

The smashed ruins of Herod's grave. Guess he doesn't even have a grave to roll in any more.

The smashed ruins of Herod's grave. Guess he doesn't even have a grave to roll in any more. A sloped wall set as backdrop to Herod's tomb. Orignially, the entire structure was walled with these smoothe stones.

A sloped wall set as backdrop to Herod's tomb. Orignially, the entire structure was walled with these smoothe stones.

From the Herodion one can see the historic hillsides, Bedouin villages, and the renewed Jewish presence, of the Etzion region.

To the south is Tekoa, home village of Amos the Prophet. Despite the fact that it's outside the security barrier, the new road opened recently has reduced commute times to Jerusalem from 45 minutes to 10 minutes. Housing prices have shot up and new trailers pop up everywhere.

Tekoa

Another settlement, Noqdim, is southeast.

Small patches of trailers mark the new areas settled by the residents of Noqdim. Out into the distance are the rolling hills of Judea. In the far distance, on a clear day, you can see the Herodion.

Small patches of trailers mark the new areas settled by the residents of Noqdim. Out into the distance are the rolling hills of Judea. In the far distance, on a clear day, you can see the Herodion. The region is also populated by a smattering of Bedouin, now post-nomadic, who settled in the region during the Jordanian occupation, between 1948 and 1967. One trend I have noticed over the past few years is the Arabs' switch from plopping down individual houses to building massive tract-housing projects, likely something they picked up working as laborers on Jewish land developments.

The region is also populated by a smattering of Bedouin, now post-nomadic, who settled in the region during the Jordanian occupation, between 1948 and 1967. One trend I have noticed over the past few years is the Arabs' switch from plopping down individual houses to building massive tract-housing projects, likely something they picked up working as laborers on Jewish land developments. Tract housing in the middle of an Arab village. Five years ago you never saw something like that.

Tract housing in the middle of an Arab village. Five years ago you never saw something like that.After the tour, we took a break in Tequoa to see the new olive press just opened there, and to scarf down some lunch.

And that's it for the Herodion!