My writings on the Nation, Torah, and Land of Israel. To see my artwork, please visit Painting Israel.

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Matchmaker, Matchmaker

“Hi my name’s Michael, and this is my wife…”

“… Sarah,” she finishes for him. “We haven’t seen you here before.”

His mission on this Earth now discharged, Michael submissively bows his head and tries to drift off.

“Well, I moved into town three months ago,” I respond.

Now she’s perked up. I’m potentially single guy, and I’m local. Blood in the water!

“Where are you from what do you do?”

“Walnut Creek, California. I’m an engineer.”

And now to work the conversation towards the real question. It’s a delicate question and must be asked with tact and subtlety. It can come in the form of, Are you living alone? Or, Did you arrive with family?

“So are you single?”

The direct approach. This one’s been in Israel for a while.

“Yes.”

Her mind rushes into action. Single. Employed. Not a psychopath. Her eyes glaze over as she re-routes all available brain power to scanning her mental rolodex of single girls. At this point, I could say just about anything. I try to make conversation to fill the dead air.

“You know, the hills sure are steep here in Jerusalem. It’s tough to ride my bike.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Did I mention that I’m a world-class athelete? I took home gold in the water balloon toss in the 2003 Fall Olympics.”

“Uh-huh.”

“And in my spare time I’ve genetically modified the Holstein cow to excrete four different flavors of ice cream, one from each teat.”

“Uh-huh”

“And I’ve…”

*BING* The glaze vanishes from her eyes. Her mental search has yielded a fruit. “I think I know someone you might be interested in.”

Next comes the glowing description, followed by a strong personal recommendation.

“My husband will call you Motzei Shabbat.” (Saturday night.)

Sometimes she forgets and I don’t have her name, so the opportunity is lost.

Sometimes, she calls me back with a negative answer.

“She said she’s not interested right now.”

“She’s out of town for the next month.”

“I didn’t realize she’s married with four kids already.”

But once in a while, I get a positive lead, and a phone number. Then comes the first phone call.

Ring…

I’m praying she doesn’t pick up. Just let me leave a message. It’s sooooo much easier.

Ring… “Shalom?”

“HiIgotyournamefromafriendwould-

youliketomeetsometime?”

“Wait, who are you?”

Name! Think, now, what’s my name?

“Uh… Ephraim?”

“Oh yeah, my aunt/grandmother/dermatologist told me you’d be calling. Sure.”

Score! El-Smootheo strikes again!

Next comes the first date, stammering at each other at a coffee shop over a cup of orange juice (she’s just learned I’m caffeine intolerant.) We’ll get the ball rolling with a search for common acquaintances.

“Uh… do you know Motti, the guy at the door who checks your backpack for explosives at the Immigrant Absorption Ministry?”

“I was born here. I’ve never been to the Absorption Ministry.”

“Oh. Uh… do you know Shlomi, my barber in Pisgat Ze’ev?’

“No. And what are you doing living in Pisgat Ze’ev?”

“I had cousins there and they offered to take me in until I got settled.”

“You mean you’re still living off your family?”

“NO! It didn’t come out right.”

Hmmm… best to just take a breather and sip my orange juice for a bit. Veeeeeeery slooooooowly. Let’s see if she takes a turn.

“So what did you do in the Army?” she asks.

Uh-oh. This is the big Israeli thing that I have no experience with. And I don’t really care what she did in the Army. Actually, most religious girls go through national service, but it’s still conscription, something all Israelis go through.

“Well, so far they haven’t called.”

And that’s what it usually comes to. My dates hit a roadblock, or at least a severely congested checkpoint, because I don’t share any common experiences. I don’t know if the last four years in America have fossilized me as an outsider, if it’s personality or lack of experience, but the female Israeli mindset is very difficult to navigate.

Speaking with one of my Rabbis, I hear some sage advice, “The fact that you’re a guy and she’s a girl will give you enough work, don’t add to it the fact that you’re an American and she’s an Israeli.”

But where to find immigrants? It’s time to seek professional help. Enter the matchmakers, the shadchaniyot!

Ringing the doorbell, I’m welcomed in and shuttled off to an antechamber in the apartment.

“We’re finishing up with someone else, and we will be with you in fifteen minutes. Please, make yourself comfortable.”

The waiting room even has a magazine. Talk about professional! All that’s missing is the strip of butcher paper over the bed. I feel like I should be stripping down and changing into a gown.

The door opens, “We’re ready to see you.”

The shadchaniyot crouch poised over their forms, pens at the ready. I hand over my passport photographs and references. The questions come rapid fire:

“Name?”

“Date of birth?”

“Height?”

“Religious from birth/newly religious/convert?”

“Level of religious observance?”

“How would you describe yourself?”

Next, questions about the girl you’re looking for:

”Do you want a television in the house?”

“What age range do you prefer?”

”Do you want her to cover her hair?”

“What midot (personality traits) are you looking for?”

“Don’t be shy. If you don’t tell us exactly what you’re looking for, we won’t know.”

And now, with the questioning done, it’s time for the matchmaking minds to begin working. Most communication is done telepathically, although sometimes sentence fragments slip out.

“What to you think about…”

“…Rivkah”

“My thoughts exactly.”

“But wasn’t she involved in…”

“Yes, but that was before, now it’s…”

“No, I don’t remember if that was a problem…”

“It wasn’t…”

”Now do you think he would work with Leah…”

“… no, too Israeli..”

”But she’s over… no she’s not yet.”

”Well, I think that Illana, would, you know,…”

“…yes, of course!”

Suddenly, both heads turn towards me.

“Okay, we have a list of names that we think you would go well with. We’ll call them, to make sure they’re available, and then we’ll call you.”

An hour after entering, I step back out into the cold winter night. Still single, but hope springs eternal.

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

Hebron

Yitzchak has left us to return to his wife and four children, so Sasha and I continue alone, through the ruins of the Jewish quarter, destroyed in the anti-Jewish pogrom of 1929.

"Here," Sasha says, pulling me over to what used to be a doorway, "you can still see the outline of a mezuzzah (Jewish doorpost scroll.)"

The rubble looks like something out of a post-World War II movie. Walls crumbling away, sprouting shrubbery. Some homes have been broken in half, revealing a diorama-like perspective inside.

"They left this area in ruins since 1929. The Arabs are afraid to move in here, afraid of the ghosts."

But it hasn't stopped them from plastering the area with the posters of suicide bombers and Hamas politicians.

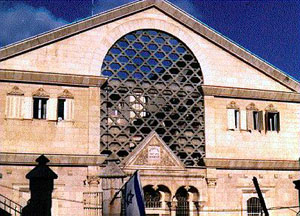

Turning the corner from the landscape of death, we are confronted with the Ma'arat Hamachpelah, the burial place of the biblical Adam and Eve, Abraham and Sarah, Isaaak and Rebecca, and Jacob and Leah, one of Judaism's holiest sites.

The building is one of several projects built by the Roman Proconsul Herod the Builder in the holy land. The massive stones reveal the same groove around their edges as the stones at the Kotel (western wall.)

After Mincha, Sasha and I head towards the Avraham Avinu (Abraham our Father) neighborhood, the section of the Jewish quarter which was rebuilt in the 1980's. We split up, he heads off to meet an artist who lives here, and I find the english tour. I know all the sights, but it's still exciting to see it all again.

There's the Avraham Avinu synagogue, demolished by the conquering Jordanian Legion in 1948 and used as an a garbage dump and animal pen until being rebuilt when Jews moved back into this area.

There's Beit Hadassah, a hospital built by Jewish philanthropists which served Arabs and Jews until 1929, now reclaimed.

There's the ancient Jewish cemetary.

And there's Tel Rumeidah, where history runs deep underfoot. Underneath stand the ruins of the ancient biblical city of Hebron, where Reut and Yishai (Ruth and Jessee) are buried, where King David was crowned and ruled for ten years, Judaism's second holiest city.

Excavations under Tel Rumeidah

Tel Rumeida has the same semi-circle of Jewish trailers, but there's something new here; a four story building. When I was last here, four years ago, the building was still in the planning stages, with lawyers and activists doing everything in their power to prevent Jews from living here. But today, here it stands.

The new building in Tel Rumeidah

The new building in Tel Rumeidah

And so, progress is slow and painful, every brick bought with suffering, and even today a cloud hangs over the entire Jewish Quarter, it being on the short list of Jewish settlements to be demolished. But it's important to remember that despite the political and physical strife surrounding this place, this is still the same holy city it's always been. And it's all a part of the same land. The mountain range which runs through the hills of the Negev desert to the south, also runs through Hebron, as it does through Jerusalem, Shechem, Elon Moreh, and clear up through the Gallilee. To understand the connection to this place, one must take a step back and see it not through the lense of politics of war, but through history, memory, and dreams for the future.

New building in Kiryat Arba

Sasha and Me

My Host Yitzchak and Me

Getting out was just as much of a madhouse as getting in.

Monday, November 27, 2006

Pictures from Harsina

Sunday, November 26, 2006

Harsina

“Gaveritye Paruski?”

“No,” Alex interjects in Hebrew, “he doesn’t speak Russian, he’s American.”

Yitzchak, shooting me a bemused look, switches to Hebrew, “You live in Israel and don’t speak Russian? How do you get by?”

“He’s only been here three months,” Sasha explains, “Give him time.”

Sasha and Alex are part of the massive wave of aliyah from Russia in the 1990s, when four million Israeli Jews assimilated one million Russian Jews in one decade. To experience the same level of strain on national resources, the United States would have to assimilate 60 million immigrants in one decade. Any other country this small would have cracked. One would especially expect a country as at running the day to day operations of government as Israel to utterly collapse. The Knesset, or parliament, is still bickering over drafting a constitution 58 years after independence, but handling overwhelming crises against impossible odds is Israel’s specialty. The country granted the newcomers immediate citizenship and mobilized to build new housing in most major cities, and in the settlements. One area which took in an infusion of new, Russian blood was the “Hebron block,” consisting of the towns of Kiryat Arba, Harsina, Givat Ha’avot, Ehsmoret Yitzchak, and the Jewish neighborhood in the center of Hebron.

Unlike Elon Moreh, perched on a mountaintop overlooking Shechem but several miles outside of the city itself, the Hebron community lives face to face with its Arab neighbors. In sum total, there are about 7,000 residents between all of the towns, but today, for the pilgrimage on Parshat Chayyei Sarah, the population swells to at least 35,000. Busses continue cruising through the gate in the fence separating us from Hebron’s 120,000 Arab residents. Other visitors pry backpacks and sleeping bags which have been crammed into the trunks of their cars. Some pitch tents in public parks.

The Streets of Harsina

The Streets of HarsinaWalking to shul, the dull red light of the sunset splashes over the Jerusalem stone houses. Friday’s last gasp. The homes, shuls, schools, and yeshivas are huddled together on the hilltop, looking across a valley of vineyards to Kiryat Arba, clinging to the next hilltop a mile or two distant.

“When was this place built?”

“Ten years ago,” Yitzchak tells me. “We started in trailers.”

“You remember the outpost I showed you in Elon Moreh?” Sasha asks. “This is what happens when we stick with it.”

Beneath the last line of houses sit two rows of new trailers. Signs of things to come?

“We wanted to build between Harsina and Kiryat Arba,” Yitzchak tells me, “but the Army won’t allow us. So they set up a base in between our two hilltops, and now nobody can build there.”

Looking from Harsina out to Kiryat Arba

The road connecting our hilltop to theirs lined on either side by a barbed wire fence, making this a cross between a trailer park and a gated community. But the fence feels like window dressing, including none of the fancy electronics, motion sensors, cameras, or trip wires that I’ve seen elsewhere. Scanning the perimeter, I detect several gaps. There are always one or two cars on the road. The flashing blue lights signal army patrols, but other vehicles, civilian, also rumble along. On Shabbat.

Foreground: Harsina trailers

Midground, left: Connecting road

Midground center: Army camp

Background: Kiryat Arba

“Yes,” Yitzchak responds to the unasked question, “We’re a mixed settlement.” Mixed religious-secular. I would later learn that you can even buy pork in Kiryat Arba, something of a rarity out here.

The crowd in shul is a warm relief from the nippy weather, visitors and locals soaking up the excitement of the evening. The rabbi begins his lesson, and I try to focus on the Hebrew. I can understand at first, but soon I miss a word. Then there’s a sentence I can’t understand, and pretty soon my logic train has derailed and my mind starts to wander, my eyes drifting around the room. To the pistol butt protruding from under the rabbi’s belt line. The rabbi’s packing heat. To several oriental faces peeking out from behind their prayer books.

“Benei Menashe,” Yitzchak explains.

After the northern ten tribes of the Kingdom of Israel were defeated by the Assyrians and dragged into exile in 721 BCE, most historians assume they were lost to assimilation. But every now and then a group pops up with peculiarly Jewish customs. In northeast India, explorers discovered a group which observes circumcision, prays wrapped in a shawl, practices levirate marriage, and offers sacrifices on biblical-style altars (the latter two practices no longer existing in contemporary halachic Judaism.) They also have a tradition of being from an ancestor named “Manmaseh,” which sounds suspiciously like the exiled tribe of Menasheh, and are familiar with several biblical stories. Due to the lack of proof surrounding their lineage, many of the Benei Menashe went through conversion according to Halachah (Jewish law,) after which they made aliyah, one of them ending up sitting in the chair next to mine.

“Actually, we have lots of converts,” Yitzchak explains to me on the way home, “I know some from Italy, one from Germany, people from all over. Right here in Harsina.”

Benei Menashe (Taken from their website)

It’s difficult explaining to someone who has never been out there why normal people who live with the same worries about families and businesses as any suburban American would choose to live out here in the territories, armed, locked behind barbed wire in a Jewish ghetto. Often, those who live here are divided into the “Quality of Life,” versus the, “Ideological” types. “Quality of Life” settlers, so it goes, moved to these places for inexpensive housing, the fresh air, and the scenic vistas, whereas “Ideological” settlers are those who came here out of conviction and belief, what some consider “fanaticism.” But to differentiate misses the point, that the quality of life is in many ways dependant on the idealism of the community. Unlike life in the rest of Israel, in the settlements, drug use is extremely rare, and burglary isn’t an issue. Prostitution, extortion, organized crime, and teen pregnancy are unheard of. Per capita income is lower but test scores are higher, and the settlements have the highest birth rate of any group in Israel. A reasonable comparison could be made between the Harsina townspeople and the American military. Many of those who serve in the American military do so to earn money for college, advance their careers, and see the world, while others come for action or to fulfill a patriotic duty. But to say that “Quality of Life” soldiers are not ideological as well is simply untrue. Dedication to a noble cause breeds excellence of character. As for the communities here in Hebron, one can pick instances of fanaticism or instability from the last 40 years of headlines, but it doesn’t characterize anyone I’ve ever met, and it’s certainly not unique to this particular segment of Israeli society.

To be continued…

Saturday, November 25, 2006

Thanksgiving in Israel

Back in the states, thanksgiving is one of those holidays Jews can celebrate, for the most part. The big one, Christmas, is out, as are Easter and Valentine’s day, due to their Christian origins. And for most observant Jews, 4th of July, Memorial Day, Labor Day, while respected, are a pale second to the Jewish holidays. While some rabinnic authorities oppose the celebration of thanksgiving as “imitating the ways of the Goyim (natons,)” most believe the holiday to be perfectly acceptable.

I’ve always loved Thanksgiving, the idea of gratitude being basic to Judaism. The very word Jew is based on the Hebrew “Yehudi,” which comes from the name of the Jewish tribe from which most of us descend, the tribe of Yehuda, a name which is rooted in the verb “Lehodot,” “To Thank,” meaning that a Jew is one constantly thanking God .

The pilgrims themselves saw themselves as analogous to the children of Israel, fleeing from the religious repression of Pharaoh (in their case, the Church of England,) and viewed their trans-Atlantic voyage as the crossing of the Red Sea, taking them to the promised land.

Thanksgiving is, in fact, based on the “Festival of Booths,” or “Feast of the Tabernacles,” which Jews call Sukkot. Likewise, while European Christianity busied itself persecuting and killing innocent Jews, America was positively philo-Semitic. Many of the earliest required working knowledge of biblical Hebrew, and one could even write their thesis in Hebrew.

I know of Jews who escaped the Holocaust to Israel, only to find they couldn’t adjust and returned to Germany after the war ended. Just imagine the schitzoid self-hatred they must experience. One thing to be thankful for is that I come from a country which, unlike Europe and the Arab world, is not blood-stained by mellinia of anti-Semitism. Living in a homeland that isn’t my birthland, as sort of American-Jewish pilgrim, I’m reminded on a daily basis of my status as an outsider, and there’s always a longing for the familiar tastes of home. Thank God for Turkey.

I took a few pictures on the way to Ricks house, posted below.

Sunset in Pisgat Ze'ev

Transferring busses at Bar Illan intersection, a major crossroads and Haredi (ultra-orthodox) neighborhood.

Transferring busses at Bar Illan intersection, a major crossroads and Haredi (ultra-orthodox) neighborhood. Looking back at the city from Ramot, where my friend Rick lives.

Looking back at the city from Ramot, where my friend Rick lives. Rochelle, Rick's wife, carves the turkey.

Rochelle, Rick's wife, carves the turkey.

The lit building is the Belzer World Center. Built by the Belzer Chassidim, it is designed to look like the Beit Hamikdash (the holy temple in Jerusalem.) Some day soon, we'll have the real thing up and running.

The lit building is the Belzer World Center. Built by the Belzer Chassidim, it is designed to look like the Beit Hamikdash (the holy temple in Jerusalem.) Some day soon, we'll have the real thing up and running.

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

Shabbat Chayyei Sarah in Hebron

Disembarking from the local bus, heading for the inter-city busses.

Disembarking from the local bus, heading for the inter-city busses.

Continuing south, we passed around Beit Lechem, through the tunnel, and out to the Gush Etzion settlement block. The settlements were rebuilt on the ruins of Jewish communities destroyed by the Jordanian legion in their 1948 invasion of Israel. Today, the population in the rebuilt towns and villages is booming, in what used to be an agricultural area but is today fast becoming a major suburb of Jerusalem.

The blue on the map above is Gush Etzion

Efrat

Efrat More Efrat

More Efrat

Vineyards

Vineyards

Fallow fields and farmland.

Gradually, the landscape again becomes crowded, as we approach Hebron. The bus turns west, passes through the security gate, and we have arrived. Our host family lives in Harsina, a Jewish suburb of Hebron.

The bus stop in Harsina

Signs welcoming visitors

Stay tuned for more!