Yitzchak has left us to return to his wife and four children, so Sasha and I continue alone, through the ruins of the Jewish quarter, destroyed in the anti-Jewish pogrom of 1929.

"Here," Sasha says, pulling me over to what used to be a doorway, "you can still see the outline of a mezuzzah (Jewish doorpost scroll.)"

The rubble looks like something out of a post-World War II movie. Walls crumbling away, sprouting shrubbery. Some homes have been broken in half, revealing a diorama-like perspective inside.

"They left this area in ruins since 1929. The Arabs are afraid to move in here, afraid of the ghosts."

But it hasn't stopped them from plastering the area with the posters of suicide bombers and Hamas politicians.

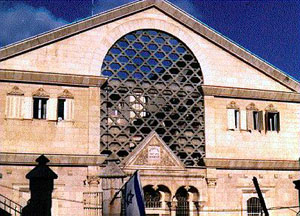

Turning the corner from the landscape of death, we are confronted with the Ma'arat Hamachpelah, the burial place of the biblical Adam and Eve, Abraham and Sarah, Isaaak and Rebecca, and Jacob and Leah, one of Judaism's holiest sites.

The building is one of several projects built by the Roman Proconsul Herod the Builder in the holy land. The massive stones reveal the same groove around their edges as the stones at the Kotel (western wall.)

After Mincha, Sasha and I head towards the Avraham Avinu (Abraham our Father) neighborhood, the section of the Jewish quarter which was rebuilt in the 1980's. We split up, he heads off to meet an artist who lives here, and I find the english tour. I know all the sights, but it's still exciting to see it all again.

There's the Avraham Avinu synagogue, demolished by the conquering Jordanian Legion in 1948 and used as an a garbage dump and animal pen until being rebuilt when Jews moved back into this area.

There's Beit Hadassah, a hospital built by Jewish philanthropists which served Arabs and Jews until 1929, now reclaimed.

There's the ancient Jewish cemetary.

And there's Tel Rumeidah, where history runs deep underfoot. Underneath stand the ruins of the ancient biblical city of Hebron, where Reut and Yishai (Ruth and Jessee) are buried, where King David was crowned and ruled for ten years, Judaism's second holiest city.

Excavations under Tel Rumeidah

Tel Rumeida has the same semi-circle of Jewish trailers, but there's something new here; a four story building. When I was last here, four years ago, the building was still in the planning stages, with lawyers and activists doing everything in their power to prevent Jews from living here. But today, here it stands.

The new building in Tel Rumeidah

The new building in Tel Rumeidah

And so, progress is slow and painful, every brick bought with suffering, and even today a cloud hangs over the entire Jewish Quarter, it being on the short list of Jewish settlements to be demolished. But it's important to remember that despite the political and physical strife surrounding this place, this is still the same holy city it's always been. And it's all a part of the same land. The mountain range which runs through the hills of the Negev desert to the south, also runs through Hebron, as it does through Jerusalem, Shechem, Elon Moreh, and clear up through the Gallilee. To understand the connection to this place, one must take a step back and see it not through the lense of politics of war, but through history, memory, and dreams for the future.

New building in Kiryat Arba

Sasha and Me

My Host Yitzchak and Me

Getting out was just as much of a madhouse as getting in.

No comments:

Post a Comment